Developed Medical Imaging (DMI): Turning Malawi’s Imaging Gaps into a Blueprint for Care

In a Ministry of Health conference room in Lilongwe, the agenda is practical to the point of austere: where to put ultrasound rooms, how to keep X-ray units running, who signs off on radiation safety, and how to measure if any of it works. Around the table sit radiologists, radiographers, sonographers, a cardiologist, and health officials. This is Developed Medical Imaging (DMI)—a Malawian NGO—at its most itself: local specialists mapping the unglamorous steps that make diagnostic services faster, safer, and fairer.

Malawi’s imaging landscape has long been shaped by scarcity and improvisation. Infrastructure is thin, equipment is patchy, funding is tight, partner coordination is inconsistent, and standards are either outdated or applied unevenly. The consequences are visible in waiting rooms and ward rounds. Without clear governance and maintenance, machines drift in and out of service. Without designated ultrasound suites, scans get squeezed into X-ray rooms, forcing staff to toggle between modalities and patients to wait longer than they should. Radiation protection too often rests on habit rather than up-to-date guidance.

DMI’s proposition is straightforward: treat imaging as essential care, and run it with the same discipline you’d expect in an operating theatre. That starts with basics—standard operating procedures, radiation safety protocols, designated ultrasound rooms, and maintenance and uptime plans—and extends to the systems that keep basics from slipping: supervision, quality audits, and data that are actually used, not simply collected.

The clinical canvas is broad. Across government and mission facilities, Malawi delivers general and special radiography, ultrasound, CT, mammography, and MRI. But the next frontier remains out of reach: interventional radiology, nuclear medicine, and radiotherapy. The absence matters. Without interventional services, some emergencies stay surgical when a catheter could do; without nuclear medicine, certain cancers and cardiac conditions are harder to stage; without radiotherapy, oncology care is perpetually incomplete. DMI isn’t romantic about timelines, but it is precise about sequence: stabilize today’s services, train tomorrow’s workforce, and plan the leap to advanced modalities with eyes wide open about power, parts, and people.

To make that arc real, DMI has spent the last few years doing coalition work. In early 2021, it partnered with MTIMA to secure targeted financial, technological, and educational support—especially for diagnostic cardiac imaging. Echocardiography is the perfect test case: high clinical value, comparatively affordable, and exquisitely sensitive to training and process. Together, DMI and MTIMA built hands-on echo programs with measurement discipline, structured reporting, and peer review—so images don’t just look better, they change decisions.

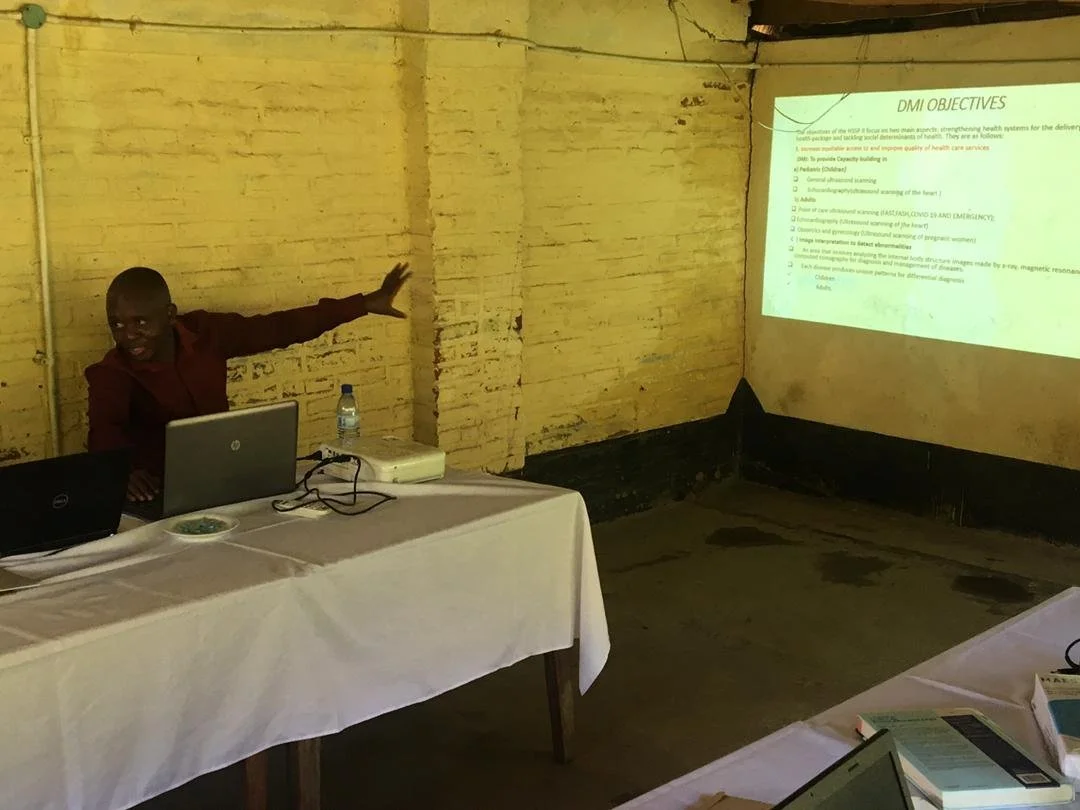

DMI Team

At the same time, DMI moved upstream into education, working with Mzuzu University and the College of Health Sciences to help shape degree-level diagnostic imaging programs. The point isn’t a logo on a curriculum. It’s a pipeline: technicians trained to diploma standards, radiographers trained to degree standards, supervisors capable of running audits and teaching juniors, and a cohort ready to anchor the country’s future in ultrasonography, MRI, interventional techniques, nuclear medicine, and mammography. When you train in Malawi for Malawi, continuity becomes a feature, not a fluke.

The government relationship is the other pillar. Meetings with the Ministry of Health are less about promises than permissions: aligning procurement with service contracts, agreeing on room specifications and radiation controls, clarifying referral pathways between district hospitals and central sites. Policy without pipes is poetry; DMI’s work is plumbing—connecting decisions to doorways, machines to maintenance, training to bedside.

DMI meeting with Ministry of Health

What does success look like at ground level? A patient in a district hospital is triaged with ultrasound in a room designed for it, not borrowed for it. The radiographer isn’t forced to choose between an X-ray queue and an echo queue because the service runs in parallel, not in conflict. A structured report lands on a clinician’s desk with a conclusion that guides action—refer now, treat here, follow-up then. Radiation badges are worn and monitored as a matter of course. A broken probe is swapped, repaired, and logged because a spare existed and a contract was signed. None of this makes for dramatic ribbon-cuttings. All of it makes the queue move.

It also widens the frame for cardiac care. With echo skills in local hands and reporting standardized, heart-failure patients find diuretics and follow-up sooner; suspected valve disease reaches specialist review faster; possible ACS cases are funneled through clearer decision trees. Minutes saved in imaging become beds freed on the ward. When minutes and beds compound, systems breathe.

The ambition doesn’t stop at the ward door. DMI’s vision reads bold on paper—timely, cost-efficient, high-quality imaging for a diverse patient population; high-quality training for the workforce—but the organization’s temperament is closer to an engineer than a marketer. Start with what you can measure. Fix the room. Secure the parts. Train the person. Audit the result. Then do it again next month.