COVID-19 in Malawi: A Hard Year, A Clearer Mandate for Heart Health

The first confirmations came on April 2, 2020—three cases announced in Lilongwe, a quiet start to a long season of vigilance. Within weeks the virus had touched every district, and a health system already stretched by infectious disease and a rising tide of non-communicable illness had to pivot on a dime.

Policy moved fast. Before a single case, the government declared a national disaster, banned large gatherings, and closed schools. A 21-day lockdown announced for mid-April was quickly halted by the High Court after civil society warned it would punish Malawians living hand-to-mouth. The message was not denial but calibration: fight the virus without breaking the people. That balance—epidemiology in one hand, economics in the other—shaped everything that followed.

Hospitals adapted with the tools they had. Oxygen concentrators multiplied. Triage tents appeared. Duty rosters flexed around power cuts and quarantines. Transmission stayed stubborn even as fatality rates remained below worst-case fears. When vaccines arrived, the goal wasn’t a victory lap; it was oxygen today, bed turnover tomorrow, endurance all year.

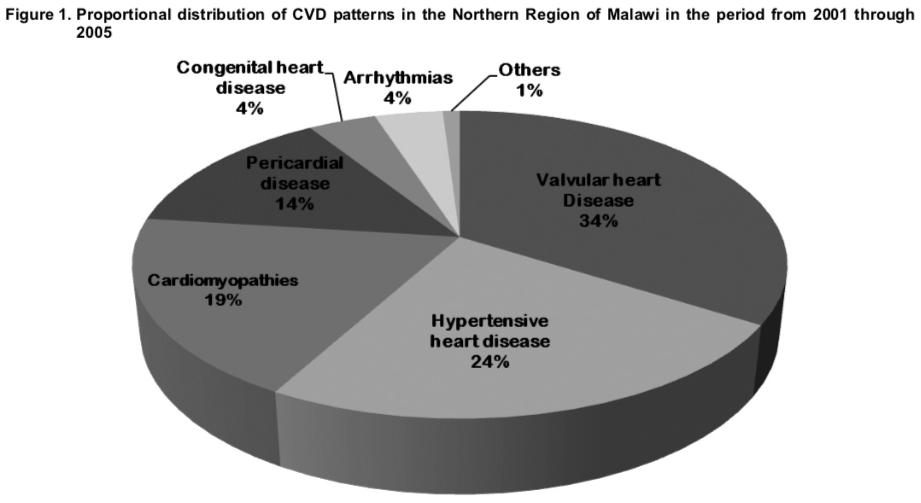

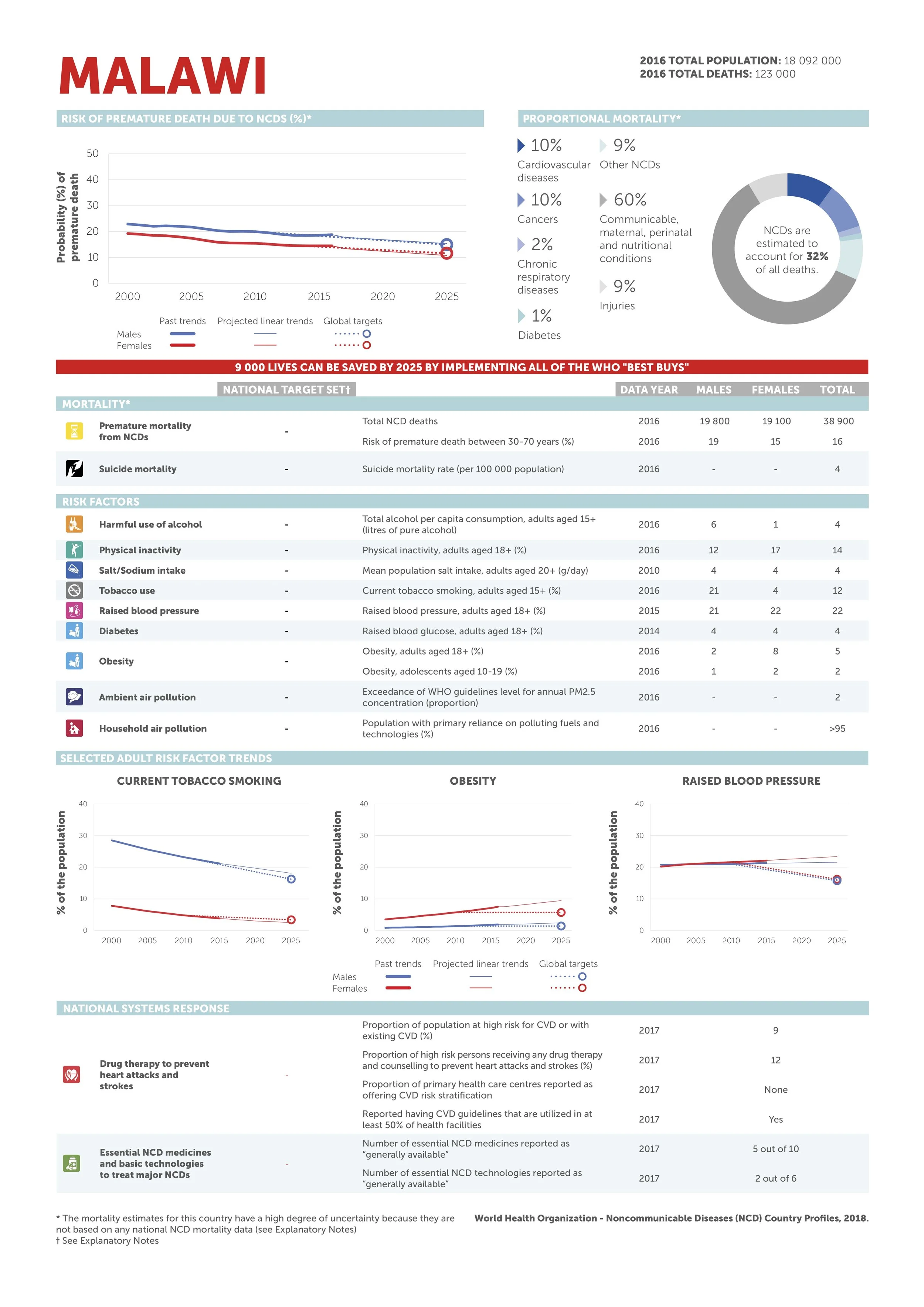

COVID did not pause Malawi’s other health emergency. Non-communicable diseases now account for a large and rising share of deaths, with cardiovascular disease threaded through clinics and waiting rooms. Coronary artery disease is not the whole story—rheumatic valve disease and heart failure remain common—but CAD’s risk profile is sharpening as hypertension, diabetes, and urban lifestyles outpace the clinics meant to manage them. The practical consequence is familiar to every outpatient department: more chest pain that deserves timely triage, and too many patients getting it late.

Malawi’s health system is principled and pragmatic. Public care is free at the point of use; mission and private facilities fill gaps; donors stitch in scaffolding when budgets fray. What’s scarce, beyond money, is time—time to acquire a clean echocardiogram, time to decide whether that ST-segment warrants transfer, time to pivot a heart-failure patient toward diuretics, salt counseling, and follow-up instead of another unplanned admission.

This is the seam where MTIMA works, and where its approach has felt especially relevant after the pandemic’s stress test. The model is deliberately unglamorous: build diagnostic muscle that lasts.

Training that sticks. Hands-on echo instruction in Blantyre and Lilongwe focuses on acquisition discipline—standard views, Doppler reproducibility—and on reports a clinical officer can act on at 3 p.m., not just admire at a conference.

Pathways that shorten delay. Simple algorithms turn “possible ACS” into a decision tree: who needs urgent transfer, who needs echo today, who needs risk-factor management and a clear return plan.

Quality loops, not one-off workshops. Peer review for tricky scans, case conferences that reopen the hardest studies, and templates that prevent ambiguous conclusions—all engineered for clinics that run on grit and generators, not perfect bandwidth.

Technology plays a role, but not as a mascot. Platforms are chosen for durability and serviceability. Data collection is built for busy Tuesdays, not glossy reports. Prevention runs alongside capacity-building: community education, pragmatic screening, and earlier detection so the best emergency is the one that never arrives.

The impact shows up in small, durable metrics that matter: fewer repeat scans because images are right the first time; faster referrals because reports are unambiguous; earlier heart-failure and valve interventions that send parents back to work and students back to class. Minutes reclaimed from uncertainty become beds freed on the ward. When minutes add up, the hospital breathes.

COVID-19 didn’t change Malawi’s direction so much as underline it. The country needs care that is reliable on a bad day and better on a good one. For cardiac disease, that means echo skills in local hands, pathways that don’t depend on luck, and decisions grounded in usable data. MTIMA’s bet is straightforward and stubborn: competence compounds. One trained clinician accelerates a ward. One working pathway frees an ambulance. One clear report prevents a bounce-back. The headlines may fade. The habit of precision is the story that lasts.