Malawi: Warmth, Work, and the Wide Horizon

Stretch a finger down the map of southeastern Africa and you’ll trace Malawi—a slender country ringed by neighbors (Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the northeast, Mozambique along the east and south) and anchored by a lake so vast it behaves like an inland sea. The nickname fits: “The Warm Heart of Africa” is not marketing so much as muscle memory. Greetings stretch longer here. Strangers help you find your way. The welcome is policy and practice.

Geography does some of the storytelling. Lake Malawi—one-third of the nation’s surface—feeds nets, markets, and imaginations. Inland, Mount Mulanje’s granite shoulders catch the weather and the eye. Lilongwe is the capital and largest city; Blantyre hums with commerce; Mzuzu steadies the north; Zomba, the former capital, keeps its scholarly poise. It’s a compact country with a big vertical sweep.

Malawi is also young and growing fast—more than 18 million people, most of them living in rural communities. The economy leans heavily on agriculture (think maize, tea, tobacco, sugar), which means climate shocks and price swings hit hard. External aid has long bridged the gap between public ambition and public revenue. That reliance has ebbed and flowed, but the core challenge endures: build a system sturdy enough to stand on its own.

Progress, however, is not a rumor. In classrooms, youth literacy has climbed this century—helped by sturdier buildings, better learning materials, and school feeding programs that turn hunger into attendance. Then comes the cliff: only about a quarter of young people make it into secondary school, with boys outnumbering girls. The reasons are painfully practical—household economics—and painfully preventable—safety risks on long walks to class, where girls face higher exposure to gender-based violence. Policy commitments are real; the distance between policy and daily life is real, too.

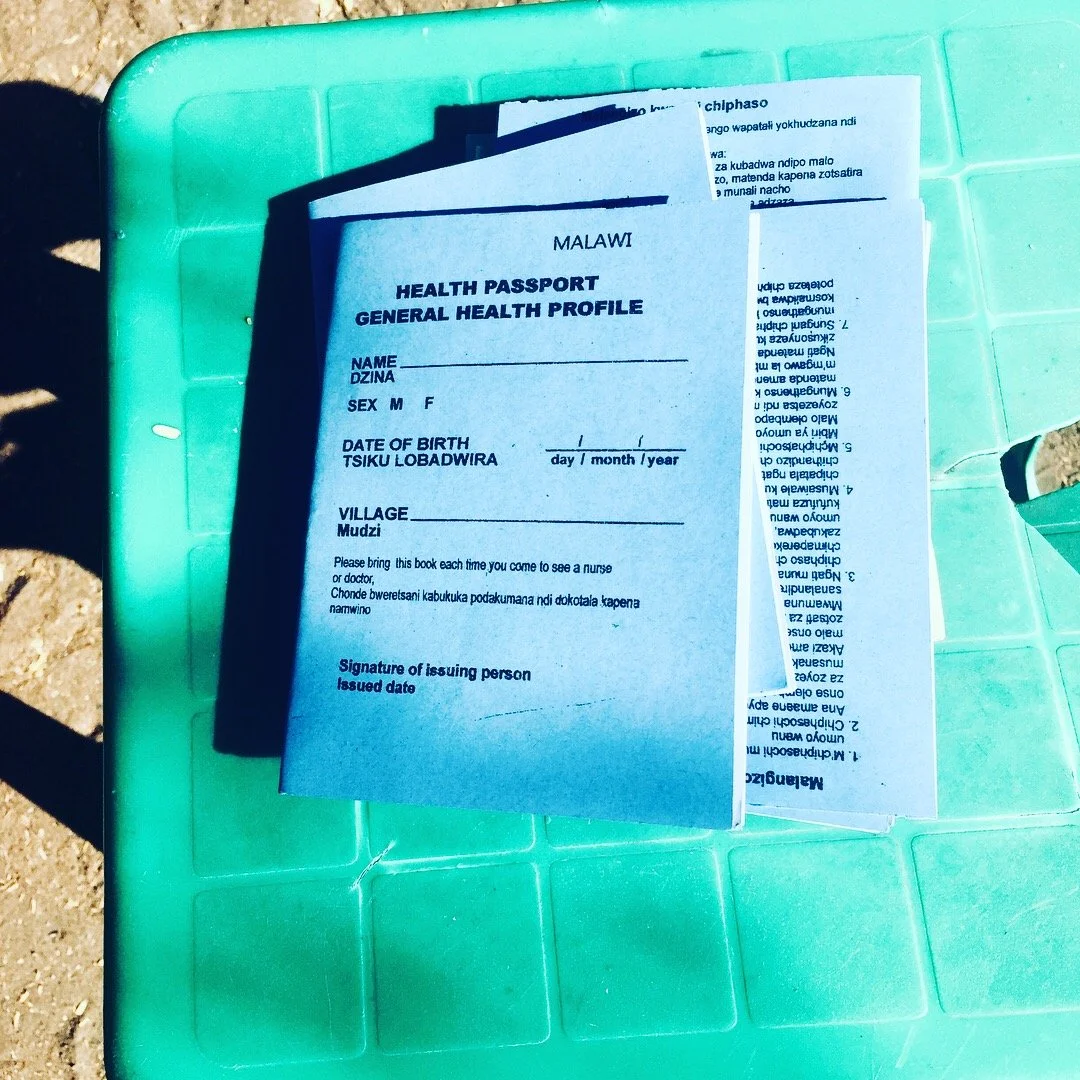

Health follows the same, stubborn pattern: low life expectancy, high infant mortality—and genuine gains where focus has been sustained. Malawi has bent the curves on child mortality and fought back against HIV and malaria through primary care, vaccinations, and relentless community work. Maternal mortality remains too high, and gender equity remains unfinished business. Systems succeed only at the pace that women can safely give birth and girls can safely stay in school.

Care is delivered through a mesh of central hospitals, district facilities, health centres, and mission and private providers. The public sector offers care free at the point of use—a principled promise that collides daily with stock-outs, staff shortages, and shaky power. Non-government partners step in, sometimes with modest fees that help them function but can nudge the poorest patients to the margins. At places like Mulanje Mission Hospital, you can hear the compromise in the drone of a generator keeping the theatre lights on and see the ingenuity in a nurse’s ledger that untangles the morning queue.

“Least-developed” is a statistical category, not a destiny. The real story lives in the ordinary miracles of competence taking root: a sonographer who can acquire and interpret a difficult echocardiogram; a clinical officer who knows when to escalate a heart-failure case; a district team that nudges referrals from rumor to diagnosis to treatment. When those skills stick—when they outlast a training week or an outside grant—the system gains muscle.

This is where organizations like MTIMA choose to work: at the seam between human warmth and technical rigor. The approach is deliberately unglamorous—train local clinicians, standardize quality, tighten referral pathways, collect usable data, repeat. Impact shows up in fewer repeat scans, clearer reports, earlier interventions. It looks like a parent back at work, a student back in class, a ward that moves a little faster because images are clearer and decisions are cleaner.

Malawi resists flattening. It’s lakeshore dawns and market laughter; it’s exam rooms doubling as classrooms; it’s a public ethic that insists health and learning are rights, not luxuries. The path forward will not be cinematic. It will be cumulative: a safer walk to school, a steadier power line to the clinic, a better protocol for the next patient with shortness of breath.

The lesson for global health is simple and demanding. Warmth is not soft; it’s infrastructure. Resolve is not loud; it’s daily. Match both with tools that work and commitments that last, and the future stops feeling theoretical. It starts looking like a docket of patients seen, a ledger that balances, and a country moving—incrementally, insistently—toward the wide horizon it has already named.